The Great Attractor

The Great Attractor

The Great Attractor

Written by

Written by

Written by

Walter De Brouwer

Walter De Brouwer

Posted on

Posted on

Posted on

Aug 9, 2025

Aug 9, 2025

Aug 9, 2025

Read

Read on Substack

Read on Substack

As a child, I first learned about the Great Attractor and how gravity and dark energy steer the Milky Way toward a destiny we can only sense, not control.

Being a passenger without a roadmap, I felt a profound sense of excitement and powerlessness. In much the same way, today’s AI landscape inspires unease: we dissect every new paper, yet nobody seems to know where we are going or what we are going to do, once we get there.

What if the strange attractor of AI isn't merely incremental hype, but a force with a greater ambition—an engine capable of unifying the sciences in a way that humanity could not complete?

The buzz we hear now is confined to local maxima. But are we bold enough to imagine and reach the global maximum? Let’s have some more coffee and think about this.

1. WILL AI UNIFY SCIENCES?

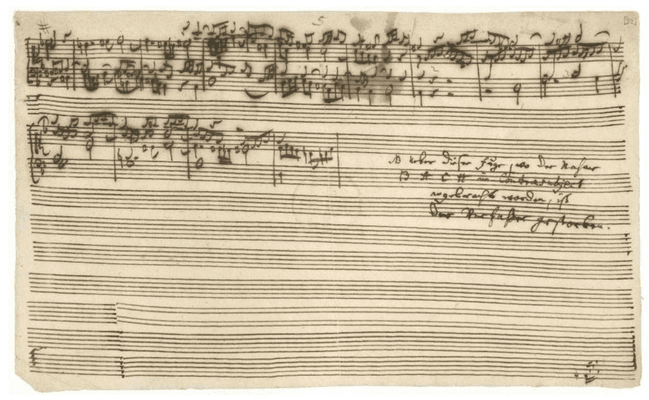

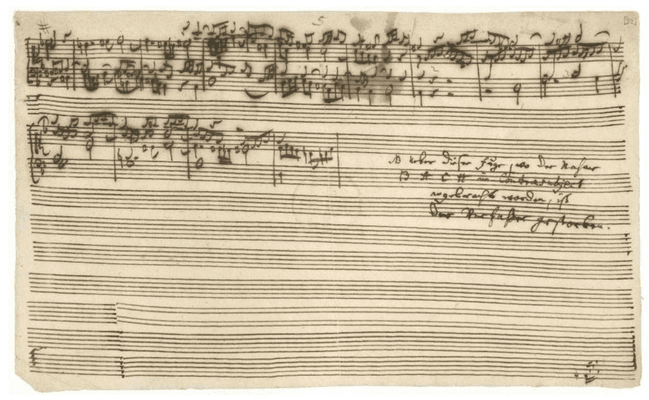

Remember when Johann Sebastian Bach’s Art of the Fugue halts mid-phrase⁽¹⁾, the last fugue spelling B-A-C-H before silence? It is both elegy and dare: Finish this, Become me. AI issues a similar provocation: if it can learn enough, the map and the maker converge. We lose the territory while building the map. Admittedly, the unfinished fugue is a testament to a life's work cut short. Its value lies as much in its incompleteness as in its existing notes.

Many promises underscore AI’s potential to unify disparate domains and to bring a multiscale vision by connecting the detail with the larger design. But most efforts focus on the beginning and others on the end but few are able to connect these.

Physics. The Standard Model explains the subatomic, and General Relativity governs the cosmic, but quantum gravity remains a wallflower, waiting for its place. A temporally‑neutral AI might find a place for it. There is of course the risk of AI entrenching a flawed “unified theory”, which we cannot disprove.

Economics. We understand how microeconomics works and how macroeconomics works, but when we try to connect them, they seem to conflict. Imagine a digital twin of the global economy where a policy tweak ripples from household to planet in one simulation pass.

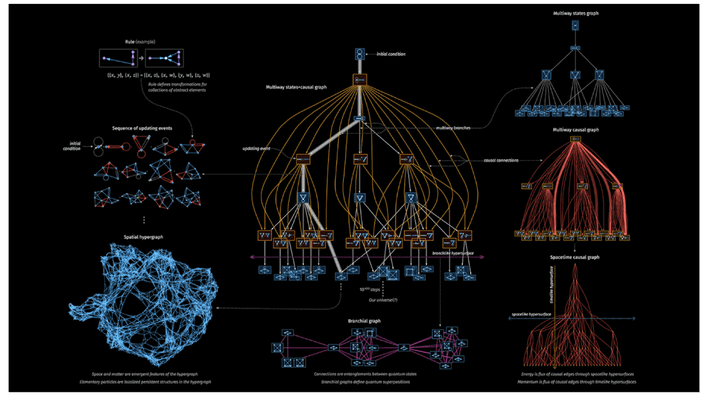

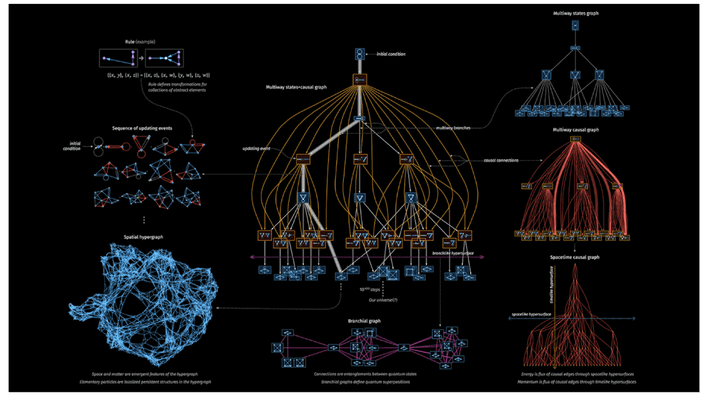

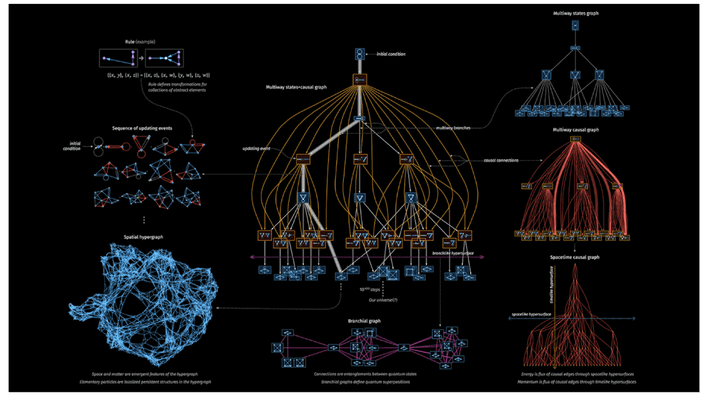

Computational Theory. While earlier thinkers hinted at connections between computation and physics⁽²⁾, Stephen Wolfram was among the first to systematically attempt a computational theory of everything. Wolfram delivered an iconic TED talk in San Francisco in 2023: “How to think computationally about AI and everything”⁽³⁾.

“And gradually things were becoming clearer. We found an outline derivation of my late friend and mentor Richard Feynman’s path integral. We started seeing some deep structural connections between relativity and quantum mechanics. Everything just started falling into place. All those things I’d known about in physics for nearly 50 years—and finally we had a way to see not just what was true, but why”.

Unifying vast fields of knowledge is one challenge; sustaining the focus to cross the finish line is another, a uniquely human struggle that AI is poised to solve.

2. WILL AI COMPLETE HUMANITY'S "UNFINISHED" WORK?

We are a start-up species, brilliant at openings and finales, but notorious for giving up in the Midpoint Slump⁽⁴⁾ (Connie Gersick, MIT). Short lives and dopamine drives make us restless. We chronically underestimate the slog phase (Planning Fallacy).

Motivation science calls it the goal‑gradient effect: effort spikes near a finish line and at a fresh start, then sags (Clark Hull in the 1930s). Dopamine follows the same U‑curve: novelty excites it, closure rewards it, routine starves it.

Janus, the Roman two-faced (he could see future and past) God of beginnings and endings, transitions, and time itself.

AI-driven platforms weaponise and exploit that sag (slump) with unearned dopamine.: micro‑bursts from infinite scroll, notification pings, or a chatbot’s instant validation or invitation to read more from the buffet of its infinite memory. The goal is not to educate us but to keep the reward circuitry firing.

The pattern mimics slot-machine conditioning⁽⁵⁾ and is now well-documented in social-media and chatbot studies as unearned dopamine. These hits feel like progress yet build no mastery. By contrast, earned dopamine arrives after the long slog—completing a paper, finishing a symphony, shipping a product.

AI can solve this, because it feels no such hunger. It does not tire of repetition.

A machine achieves a state of operational equilibrium when its gradient is constant, a functional parallel to what we might call contentment (≈happiness). AIs are temporally neutral: clock cycles do not celebrate beginnings nor endings; they simply iterate. That neutrality turns machines into natural finishers. AI lacks cravings and deadlines; it just finishes.

While our “Janus nature” supplies sparks of invention and visions of the prize, AI carries ideas across the dull plain between them. Together, the partnership could close humanity’s unfinished symphonies, from abandoned nuclear fusion models to seawater uranium extraction⁽⁶⁾ by letting silicon shoulder the stretch we historically ignore. Algorithms neither crave novelty nor fear tedium. Where Janus stops, AI begins.

3. WILL AI SHIFT CONSCIOUSNESS FROM LINEAR TO MULTIDIMENSIONAL SPACE?

In Max Richter’s On the Nature of Daylight, a string ensemble (violins, viola and cello, which could represent present, past and future) make time expand and contract⁽⁷⁾. The song was used in the movie "Arrival". The flashbacks Louise experiences, showing her daughter Hannah's life and eventual death, are not just memories, but premonitions of the future.

This is revealed as she learns the Heptapod language, which allows her to perceive time non-linearly, experiencing past, present, and future simultaneously. Their written language encodes nonlinearity itself: no strict boundaries between the three times, only what Rainer Maria Rilke called die Ewige Strömung, the eternal flow.

Perhaps the prediction of tomorrow or the next token is only an artefact and AI will dissolve the tyranny of linear sequence. Perhaps the goal is not foresight but resonance—living inside multidimensional time and space. This could manifest as a research tool that doesn't just show a scientist the next step in a sequence, but reveals a web of simultaneous, interconnected, possibilities from other fields, collapsing the time between discovery and application

Our children and grandchildren will live in a world that is in sync. We on the other hand will have lived most of our lives, out of sync: our technological and social worlds often mismatched with our evolving biological and neurological rhythms. With AI, our environment might synchronize seamlessly with our innermost selves, responding fluidly to our changing moods, thoughts, and biological states.

What will it mean for us to exist in perfect synchronization with our surroundings? Might such harmony make us part of a greater, interconnected rhythm and resonance we have yet to fully comprehend? Is something profound awaiting beyond our losses?

Epilogue.

It took 100,000 years for Homo sapiens to find company outside the black box of

a skull. Now another intelligence converses with us daily. Together we might close more research than we leave unfinished.

Perhaps this is where we are headed: not to predict the future, but to dissolve it. Not to linearize knowledge, but to live inside its multidimensional resonance. What we stand to gain, and what we might lose, in ending our ancient solitude remains a profound and compelling mystery.

"The art of losing isn't hard to master; so many things seem filled with the intent to be lost that their loss is no disaster." Elizabeth Bishop (1911-1979), One Art.

References:

J.S. Bach, “Die Kunst der Fuge” (The Art of Fugue) (1740s). Bach died before completing the final fugue, Contrapunctus XIV, which embeds his own name in the music. Listen here.

Philosophers of physics like David Deutsch, Roger Penrose, and Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker made early contributions that touched on information, physics, and computation.

Stephen Wolfram, October 2023, San Francisco: TED Talk.

The midpoint slump theory, proposed by Connie Gersick, pertains to group development and team dynamics. Gersick's research suggests that teams tend to experience a significant shift in performance or focus around the midpoint of their task or project timeline.

Psychological techniques, including both classical and operant conditioning, that casinos use to make slot machines highly addictive. These techniques exploit the brain's reward system to encourage players to keep playing, even when they are losing.

Oceans contain trace amounts of uranium that could be extracted and used as nuclear fuel.

Max Richter, “On the Nature of Daylight” (2004). Listen here

As a child, I first learned about the Great Attractor and how gravity and dark energy steer the Milky Way toward a destiny we can only sense, not control.

Being a passenger without a roadmap, I felt a profound sense of excitement and powerlessness. In much the same way, today’s AI landscape inspires unease: we dissect every new paper, yet nobody seems to know where we are going or what we are going to do, once we get there.

What if the strange attractor of AI isn't merely incremental hype, but a force with a greater ambition—an engine capable of unifying the sciences in a way that humanity could not complete?

The buzz we hear now is confined to local maxima. But are we bold enough to imagine and reach the global maximum? Let’s have some more coffee and think about this.

1. WILL AI UNIFY SCIENCES?

Remember when Johann Sebastian Bach’s Art of the Fugue halts mid-phrase⁽¹⁾, the last fugue spelling B-A-C-H before silence? It is both elegy and dare: Finish this, Become me. AI issues a similar provocation: if it can learn enough, the map and the maker converge. We lose the territory while building the map. Admittedly, the unfinished fugue is a testament to a life's work cut short. Its value lies as much in its incompleteness as in its existing notes.

Many promises underscore AI’s potential to unify disparate domains and to bring a multiscale vision by connecting the detail with the larger design. But most efforts focus on the beginning and others on the end but few are able to connect these.

Physics. The Standard Model explains the subatomic, and General Relativity governs the cosmic, but quantum gravity remains a wallflower, waiting for its place. A temporally‑neutral AI might find a place for it. There is of course the risk of AI entrenching a flawed “unified theory”, which we cannot disprove.

Economics. We understand how microeconomics works and how macroeconomics works, but when we try to connect them, they seem to conflict. Imagine a digital twin of the global economy where a policy tweak ripples from household to planet in one simulation pass.

Computational Theory. While earlier thinkers hinted at connections between computation and physics⁽²⁾, Stephen Wolfram was among the first to systematically attempt a computational theory of everything. Wolfram delivered an iconic TED talk in San Francisco in 2023: “How to think computationally about AI and everything”⁽³⁾.

“And gradually things were becoming clearer. We found an outline derivation of my late friend and mentor Richard Feynman’s path integral. We started seeing some deep structural connections between relativity and quantum mechanics. Everything just started falling into place. All those things I’d known about in physics for nearly 50 years—and finally we had a way to see not just what was true, but why”.

Unifying vast fields of knowledge is one challenge; sustaining the focus to cross the finish line is another, a uniquely human struggle that AI is poised to solve.

2. WILL AI COMPLETE HUMANITY'S "UNFINISHED" WORK?

We are a start-up species, brilliant at openings and finales, but notorious for giving up in the Midpoint Slump⁽⁴⁾ (Connie Gersick, MIT). Short lives and dopamine drives make us restless. We chronically underestimate the slog phase (Planning Fallacy).

Motivation science calls it the goal‑gradient effect: effort spikes near a finish line and at a fresh start, then sags (Clark Hull in the 1930s). Dopamine follows the same U‑curve: novelty excites it, closure rewards it, routine starves it.

Janus, the Roman two-faced (he could see future and past) God of beginnings and endings, transitions, and time itself.

AI-driven platforms weaponise and exploit that sag (slump) with unearned dopamine.: micro‑bursts from infinite scroll, notification pings, or a chatbot’s instant validation or invitation to read more from the buffet of its infinite memory. The goal is not to educate us but to keep the reward circuitry firing.

The pattern mimics slot-machine conditioning⁽⁵⁾ and is now well-documented in social-media and chatbot studies as unearned dopamine. These hits feel like progress yet build no mastery. By contrast, earned dopamine arrives after the long slog—completing a paper, finishing a symphony, shipping a product.

AI can solve this, because it feels no such hunger. It does not tire of repetition.

A machine achieves a state of operational equilibrium when its gradient is constant, a functional parallel to what we might call contentment (≈happiness). AIs are temporally neutral: clock cycles do not celebrate beginnings nor endings; they simply iterate. That neutrality turns machines into natural finishers. AI lacks cravings and deadlines; it just finishes.

While our “Janus nature” supplies sparks of invention and visions of the prize, AI carries ideas across the dull plain between them. Together, the partnership could close humanity’s unfinished symphonies, from abandoned nuclear fusion models to seawater uranium extraction⁽⁶⁾ by letting silicon shoulder the stretch we historically ignore. Algorithms neither crave novelty nor fear tedium. Where Janus stops, AI begins.

3. WILL AI SHIFT CONSCIOUSNESS FROM LINEAR TO MULTIDIMENSIONAL SPACE?

In Max Richter’s On the Nature of Daylight, a string ensemble (violins, viola and cello, which could represent present, past and future) make time expand and contract⁽⁷⁾. The song was used in the movie "Arrival". The flashbacks Louise experiences, showing her daughter Hannah's life and eventual death, are not just memories, but premonitions of the future.

This is revealed as she learns the Heptapod language, which allows her to perceive time non-linearly, experiencing past, present, and future simultaneously. Their written language encodes nonlinearity itself: no strict boundaries between the three times, only what Rainer Maria Rilke called die Ewige Strömung, the eternal flow.

Perhaps the prediction of tomorrow or the next token is only an artefact and AI will dissolve the tyranny of linear sequence. Perhaps the goal is not foresight but resonance—living inside multidimensional time and space. This could manifest as a research tool that doesn't just show a scientist the next step in a sequence, but reveals a web of simultaneous, interconnected, possibilities from other fields, collapsing the time between discovery and application

Our children and grandchildren will live in a world that is in sync. We on the other hand will have lived most of our lives, out of sync: our technological and social worlds often mismatched with our evolving biological and neurological rhythms. With AI, our environment might synchronize seamlessly with our innermost selves, responding fluidly to our changing moods, thoughts, and biological states.

What will it mean for us to exist in perfect synchronization with our surroundings? Might such harmony make us part of a greater, interconnected rhythm and resonance we have yet to fully comprehend? Is something profound awaiting beyond our losses?

Epilogue.

It took 100,000 years for Homo sapiens to find company outside the black box of

a skull. Now another intelligence converses with us daily. Together we might close more research than we leave unfinished.

Perhaps this is where we are headed: not to predict the future, but to dissolve it. Not to linearize knowledge, but to live inside its multidimensional resonance. What we stand to gain, and what we might lose, in ending our ancient solitude remains a profound and compelling mystery.

"The art of losing isn't hard to master; so many things seem filled with the intent to be lost that their loss is no disaster." Elizabeth Bishop (1911-1979), One Art.

References:

J.S. Bach, “Die Kunst der Fuge” (The Art of Fugue) (1740s). Bach died before completing the final fugue, Contrapunctus XIV, which embeds his own name in the music. Listen here.

Philosophers of physics like David Deutsch, Roger Penrose, and Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker made early contributions that touched on information, physics, and computation.

Stephen Wolfram, October 2023, San Francisco: TED Talk.

The midpoint slump theory, proposed by Connie Gersick, pertains to group development and team dynamics. Gersick's research suggests that teams tend to experience a significant shift in performance or focus around the midpoint of their task or project timeline.

Psychological techniques, including both classical and operant conditioning, that casinos use to make slot machines highly addictive. These techniques exploit the brain's reward system to encourage players to keep playing, even when they are losing.

Oceans contain trace amounts of uranium that could be extracted and used as nuclear fuel.

Max Richter, “On the Nature of Daylight” (2004). Listen here

As a child, I first learned about the Great Attractor and how gravity and dark energy steer the Milky Way toward a destiny we can only sense, not control.

Being a passenger without a roadmap, I felt a profound sense of excitement and powerlessness. In much the same way, today’s AI landscape inspires unease: we dissect every new paper, yet nobody seems to know where we are going or what we are going to do, once we get there.

What if the strange attractor of AI isn't merely incremental hype, but a force with a greater ambition—an engine capable of unifying the sciences in a way that humanity could not complete?

The buzz we hear now is confined to local maxima. But are we bold enough to imagine and reach the global maximum? Let’s have some more coffee and think about this.

1. WILL AI UNIFY SCIENCES?

Remember when Johann Sebastian Bach’s Art of the Fugue halts mid-phrase⁽¹⁾, the last fugue spelling B-A-C-H before silence? It is both elegy and dare: Finish this, Become me. AI issues a similar provocation: if it can learn enough, the map and the maker converge. We lose the territory while building the map. Admittedly, the unfinished fugue is a testament to a life's work cut short. Its value lies as much in its incompleteness as in its existing notes.

Many promises underscore AI’s potential to unify disparate domains and to bring a multiscale vision by connecting the detail with the larger design. But most efforts focus on the beginning and others on the end but few are able to connect these.

Physics. The Standard Model explains the subatomic, and General Relativity governs the cosmic, but quantum gravity remains a wallflower, waiting for its place. A temporally‑neutral AI might find a place for it. There is of course the risk of AI entrenching a flawed “unified theory”, which we cannot disprove.

Economics. We understand how microeconomics works and how macroeconomics works, but when we try to connect them, they seem to conflict. Imagine a digital twin of the global economy where a policy tweak ripples from household to planet in one simulation pass.

Computational Theory. While earlier thinkers hinted at connections between computation and physics⁽²⁾, Stephen Wolfram was among the first to systematically attempt a computational theory of everything. Wolfram delivered an iconic TED talk in San Francisco in 2023: “How to think computationally about AI and everything”⁽³⁾.

“And gradually things were becoming clearer. We found an outline derivation of my late friend and mentor Richard Feynman’s path integral. We started seeing some deep structural connections between relativity and quantum mechanics. Everything just started falling into place. All those things I’d known about in physics for nearly 50 years—and finally we had a way to see not just what was true, but why”.

Unifying vast fields of knowledge is one challenge; sustaining the focus to cross the finish line is another, a uniquely human struggle that AI is poised to solve.

2. WILL AI COMPLETE HUMANITY'S "UNFINISHED" WORK?

We are a start-up species, brilliant at openings and finales, but notorious for giving up in the Midpoint Slump⁽⁴⁾ (Connie Gersick, MIT). Short lives and dopamine drives make us restless. We chronically underestimate the slog phase (Planning Fallacy).

Motivation science calls it the goal‑gradient effect: effort spikes near a finish line and at a fresh start, then sags (Clark Hull in the 1930s). Dopamine follows the same U‑curve: novelty excites it, closure rewards it, routine starves it.

Janus, the Roman two-faced (he could see future and past) God of beginnings and endings, transitions, and time itself.

AI-driven platforms weaponise and exploit that sag (slump) with unearned dopamine.: micro‑bursts from infinite scroll, notification pings, or a chatbot’s instant validation or invitation to read more from the buffet of its infinite memory. The goal is not to educate us but to keep the reward circuitry firing.

The pattern mimics slot-machine conditioning⁽⁵⁾ and is now well-documented in social-media and chatbot studies as unearned dopamine. These hits feel like progress yet build no mastery. By contrast, earned dopamine arrives after the long slog—completing a paper, finishing a symphony, shipping a product.

AI can solve this, because it feels no such hunger. It does not tire of repetition.

A machine achieves a state of operational equilibrium when its gradient is constant, a functional parallel to what we might call contentment (≈happiness). AIs are temporally neutral: clock cycles do not celebrate beginnings nor endings; they simply iterate. That neutrality turns machines into natural finishers. AI lacks cravings and deadlines; it just finishes.

While our “Janus nature” supplies sparks of invention and visions of the prize, AI carries ideas across the dull plain between them. Together, the partnership could close humanity’s unfinished symphonies, from abandoned nuclear fusion models to seawater uranium extraction⁽⁶⁾ by letting silicon shoulder the stretch we historically ignore. Algorithms neither crave novelty nor fear tedium. Where Janus stops, AI begins.

3. WILL AI SHIFT CONSCIOUSNESS FROM LINEAR TO MULTIDIMENSIONAL SPACE?

In Max Richter’s On the Nature of Daylight, a string ensemble (violins, viola and cello, which could represent present, past and future) make time expand and contract⁽⁷⁾. The song was used in the movie "Arrival". The flashbacks Louise experiences, showing her daughter Hannah's life and eventual death, are not just memories, but premonitions of the future.

This is revealed as she learns the Heptapod language, which allows her to perceive time non-linearly, experiencing past, present, and future simultaneously. Their written language encodes nonlinearity itself: no strict boundaries between the three times, only what Rainer Maria Rilke called die Ewige Strömung, the eternal flow.

Perhaps the prediction of tomorrow or the next token is only an artefact and AI will dissolve the tyranny of linear sequence. Perhaps the goal is not foresight but resonance—living inside multidimensional time and space. This could manifest as a research tool that doesn't just show a scientist the next step in a sequence, but reveals a web of simultaneous, interconnected, possibilities from other fields, collapsing the time between discovery and application

Our children and grandchildren will live in a world that is in sync. We on the other hand will have lived most of our lives, out of sync: our technological and social worlds often mismatched with our evolving biological and neurological rhythms. With AI, our environment might synchronize seamlessly with our innermost selves, responding fluidly to our changing moods, thoughts, and biological states.

What will it mean for us to exist in perfect synchronization with our surroundings? Might such harmony make us part of a greater, interconnected rhythm and resonance we have yet to fully comprehend? Is something profound awaiting beyond our losses?

Epilogue.

It took 100,000 years for Homo sapiens to find company outside the black box of

a skull. Now another intelligence converses with us daily. Together we might close more research than we leave unfinished.

Perhaps this is where we are headed: not to predict the future, but to dissolve it. Not to linearize knowledge, but to live inside its multidimensional resonance. What we stand to gain, and what we might lose, in ending our ancient solitude remains a profound and compelling mystery.

"The art of losing isn't hard to master; so many things seem filled with the intent to be lost that their loss is no disaster." Elizabeth Bishop (1911-1979), One Art.

References:

J.S. Bach, “Die Kunst der Fuge” (The Art of Fugue) (1740s). Bach died before completing the final fugue, Contrapunctus XIV, which embeds his own name in the music. Listen here.

Philosophers of physics like David Deutsch, Roger Penrose, and Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker made early contributions that touched on information, physics, and computation.

Stephen Wolfram, October 2023, San Francisco: TED Talk.

The midpoint slump theory, proposed by Connie Gersick, pertains to group development and team dynamics. Gersick's research suggests that teams tend to experience a significant shift in performance or focus around the midpoint of their task or project timeline.

Psychological techniques, including both classical and operant conditioning, that casinos use to make slot machines highly addictive. These techniques exploit the brain's reward system to encourage players to keep playing, even when they are losing.

Oceans contain trace amounts of uranium that could be extracted and used as nuclear fuel.

Max Richter, “On the Nature of Daylight” (2004). Listen here

All blogs